CAIN Web Service

Politics in PublicFreedom of Assembly and the Right to Protest

Many of the issues that surround the right to hold parades in

Northern Ireland have also, in some form or another, been raised

in Britain, and the legislation pertaining to marches has much

in common with that in England and Wales and in Scotland. Unlike

many countries the right to public political activity is not enshrined

within a Bill of Rights, rather it is based on common law. That

is, civil rights are 'protected by the principle that people have

the right to do anything which is not expressly forbidden by law'

(Hadden & Donnelly 1997:16). Yet in practice, as the right

to march and demonstrate is not enshrined in a Bill of Rights,

there have always been reasons that the authorities could use

to prevent meetings or processions, and during the twentieth century

various pieces of public order legislation have effectively superseded

common law (Card 1987: 57-80; North 1997:89-107). Legislation Public order legislation giving the police powers to restrict processions was first introduced in 1936, in large part to deal with the fascist movement in England. At the time this was opposed by civil libertarians as being profoundly 'un-British' (Townshend 1993:104-111). One of the ways that the 1936 Act tried to deal with fascism and the development of private armies was to restrict the wearing of uniforms. This had of course long been common practice in Ireland and had given particular concern to the British authorities between 1912 and 1914 with the development of the Ulster Volunteer Force. However many who wore a uniform would have been considered harmless and as such, legislation was difficult to introduce and even harder to enforce. Whilst the issues of the wearing of uniforms did not trouble the state in the long run, the right to hold meetings and processions had become governed by public order legislation and the police gained formal powers to impose conditions on events. The policing of public political events was nor without problems in the post-war period, particularly in the 1970s when anxieties were raised during the miners' strikes and demonstrations involving the National Front. But it was only in the 1980s as a result of the rioting in areas such as Brixton, Southall and Toxteth and the 1984 NUM strike that public order became a high profile issue. Policing practice was analysed, developed and influenced particularly by reports produced by Lord Scarman on disturbances both in Northern Ireland and Britain and new legislation was introduced in 1986. In his report after the riots in Brixton in 1981 Scarman had argued that: A balance has to be struck, a compromise found that will accommodate the exercise of the right to protest within a framework of public order which enables ordinary citizens, who are not protesting, to go about their business and pleasure without obstruction or inconvenience. The fact that those who are at any time concerned to secure the tranquillity of the streets are likely to be the majority must not lead us to deny the protesters their right to march; the fact that the protesters are desperately sincere and are exercising a fundamental human right must not lead us to overlook the rights of the majority. (Lord Scarman 1981 quoted Townshend 1993:149) The Scarman Report acknowledged that public order policing in Britain relied on a society in which there was some considerable degree of consensus (Townshend 1993:1 59-166). In the 1970s and I 980s such a consensus had become increasingly difficult to find. The Public Order Act 1986 increased police powers in a way that some have argued detracts from individual civil liberties (Card 1987:6). The Act requires organisers to give advance notice of a parade to the police, although many local authorities had previously required such notice and many organisers would have freely provided it. There is an exemption 'where the procession is one commonly or customarily held in the police area (or areas) in which it is proposed to be held' although there is no clear definition of what 'commonly or customarily held' means. One should note that while this differed from legal provisions in Northern Ireland, where it is the customarily held route that is specified, it might well apply to events such as Orange parades in Liverpool. The Act also allows for the Chief Constable to impose conditions upon a procession prior to an event or a senior police officer who is present at the procession. Conditions can be imposed on the grounds of the possibility of serious public disorder, serious damage to property or serious disruption to the life of the community' or if the Chief Constable believes 'the purpose, whether express or not, of the persons organising it is the intimidation of others with a view to compelling them not to do an act they have a right to do, or to do an act they have a right not to do' (8.12.1). This last criteria effectively tries to differentiate intimidation from persuasion although as we are well aware in Northern Ireland making judgements on what constitutes intimidation is not always easy. A ban on a parade can only be imposed if serious public disorder is likely and the police have insufficient powers to impose conditions to prevent the disorder. The Chief Constable has to make an application to ban processions, or a class of procession (it is not possible to ban a single procession), to the local council or borough who may approve such an order with the consent of the Home Secretary. In London, where events tend to have more national rather than local significance, the district councils are nor involved and the Commissioner of the City of London Police or the Metropolitan Police can make a banning order with the consent of the Home Secretary. Note also that it is not possible for local residents of a local authority to force a Chief Constable to impose conditions as was attempted by Lewisham Borough Council under the old legislation over a National Front march in April 1980 (Card 1987:88-92). Public assemblies do not carry the same legal restrictions as processions and no form of notice is required to hold a public meeting. Card argues that in some senses this is anomalous since protest meetings can be just as likely to cause public disorder as a procession. But the 1985 Government white paper, Review of Public Order Law, argued that it would be too substantial a restriction of freedom (meetings and assemblies apparently being deemed more important than marches) and that the administrative burden would be too great (Card 1987:82). However conditions can be imposed on assemblies by a senior police officer on the same grounds as those for a procession.

As has happened in Northern Ireland in recent years, conditions

or bans imposed on processions can be taken to judicial review.

However, it must be remembered that in the main a judicial review

does not examine the merits of a case but simply checks that correct

procedures have been followed in reaching the original decision

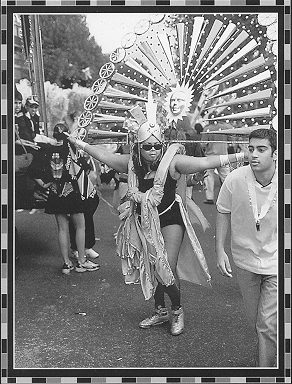

The Notting Hill Carnival The Carnival held in the Notting Hill area of London over the August bank holiday weekend involves an estimated million and a half people and is one of the largest annual public events to be held in Britain. It is the largest single routine policing operation and in the early 1990s required 9,000 officers, with costs estimated at £3 million (Waddington 1994:18). It is a complex event involving a moving parade of floats and masquerade dancers that travels a three-mile route and a number of stationary sound systems. It is highly diverse event that increasingly involves not only the ethnic Caribbean communities but also reflects the cosmopolitan, international, nature of London; Carnival draws thousands of spectators from Europe and other parts of the world. Whilst the Notting Hill Carnival has developed its own specific localised cultural forms it shares characteristics with many other similar events around the world. It is a heady pleasurable mixture of masking, anonymity, fantasy, sexuality, alcohol and other drugs. An opportunity for individuals to express themselves in ways they would feel unable to do at any other rime. It provides an occasion when social norms are abandoned or inverted. It provides a rime when some of the structures of power of the society are temporarily excluded from an area, where people masked by costume can both act anonymously and be on centre stage within a large crowd. For many participants who are allowed to dance the streets to their own rhythms it is a deeply empowering event (Alleyne-Dettmers 1996). The Development of Carnival Carnival as a general cultural form has been around for hundreds of years and has developed in a range of historical and geographical contexts. The roots of the Notting Hill Carnival can be found in Trinidad where West African slaves celebrated emancipation in 1834 by drawing on European festival and African cultural forms in public expression. Carnival provided opportunities to show political opposition and to express a public identity within the complexities of Trinidadian society (Alleyne-Dertmers 1996, van Koningsbruggen 1997). The development of a Carnival in Notting Hill stems from the influx of West Indians into the Ladbroke Grove area of west London. The area had seen race riots in 1958 and suffered growing social problems in the years that followed. There is some dispute about when and how the Carnival was started (Cohen 1993; Wills 1996), but in 1966 a multi-ethnic fair took place which over the years came to increasingly take the form of a Carnival. In 1968 the lack of support from the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea and local business led to the event being dubbed the 'Carnival of the poor'. In the 1970s racial tension increased and relations between the police and the local black community worsened, particularly with the random use of stop and search tactics on black youths. Carnival rook on more West Indian cultural forms first through Trinidadian steel bands and masquerading and then later in the decade with Jamaican Rastafarianism and reggae sound systems. In 1975 attendance reached a quarter of a million and a significant increase in crime was reported. The following year 1,500 police officers were used and they apparently acted in a high handed way, confrontations between youths and police developed and hundreds of people were injured. The violence further fractured relationships between the police and organisers but also revealed the stresses between the Trinidadian style Carnival and the more overtly politicised Jamaican Rastafarianism. The disturbances of 1976 also convinced the Metropolitan police to equip themselves with reinforced plastic riot shields (Waddington 1994:19). Relations between the police and black youths remained poor for much of the 1980s, fuelled by continuing use of stop and search tactics by the police and raids on local social centres. Each year Carnival proved a potential focus for political confrontation as well as an arena for crime. The authorities felt duty bound to provide massive policing, while the organisers regularly asked the police not to provoke the youth by appearing in large numbers. Yet whilst the organisers complained at the high profile police presence they had failed to take responsibility for maintaining order themselves. In 1977 they had hired hundreds of stewards but these were quickly over run by youths, many stewards took off their T-shirts and disappeared into the crowds. Over the years there have also been many calls from politicians to have the Carnival sited in an enclosed park or stadium. This has always been resisted by organisers who believe that it wotild change the character of Carnival. In 1986 the police introduced a new strategy with their control room 'Gold Control co-ordinating 'Silver' and Bronze divisions in the field. More streets were closed to traffic and streets in which reserve forces were kept were open only to residents. The police mingling with the crowd were instructed to turn a blind eye to minor offences. Only when large gangs started to operate did the police intervene. Yet in 1987 the number of crimes reached, as far as the police were concerned, unacceptable levels and confrontations developed after an attempted arrest. By the end of the Carnival there had been 798 reported crimes, 243 arrests (60 for the possession of offensive weapons), and 13 police officers and 76 civilians had been injured, most from gang attacks. There were the usual calls for the Carnival to be stopped and particular criticisms were aimed at organisers for providing too few stewards. In the following year there was further criticism of the organisers in a Coopers and Lybrand report paid for by the Commission for Racial Equality. The debates were concerned with the financial management of the event and the attempts to control events on the ground. Differences between various organisers over the way the Carnival should be run further complicated issues. There were no major problems at the 1988 Carnival and before the event in 1989 a new Carnival Enterprise Committee signed an agreement with the police defining the procession route, the roads to be closed, the positioning of sound systems and the time the Carnival was to close down. The Carnival was very successful until close down on the second day when a confrontation developed. The police later accepted some criticism that they had been too rigid in clearing the streets and had failed to communicate their plans to the crowd. They also agreed to replace the invasive police helicopters with a surveillance airship. The re-organisation of the running and policing of Carnival had a fundamental influence on the event itself. The number of sound systems was cur dramatically, Carnival was restricted to daylight hours and the parade route was differentiated from the areas where stationary sound systems were placed. The police established 'sterile areas' or safety zones which allow them to move around freely and also meant that police reserves, necessary to control public order, could remain largely our of view. Many saw the controls as too strict and the numbers fell in 1990. There were also fears that the commercialisation of Carnival might transform the event into something akin to the Lord Mayor's Show, and there was heated debate over the 'ownership' and origins of the event. 'Traditionalists' argued that commercialisation was changing the nature of the event and was removing it from the people of the area (Cohen 1993:74-78; Waddingron 1994). During the 1990s Carnival has further developed with sponsors providing greater funding. Since 1995 Carnival has been sponsored by the makers of the soft drink Lilt, owned by Coca Cola. There has been a greater involvement by large companies and radio stations, including BBC Radio 1 and Kiss FM, in the running of sound systems and staging live performances. By 1997 Carnival had become more ethnically diverse: Latin American, Asian and European influences have combined with West Indian and African to make the event a major tourist attraction. Compared to the 1980s there has been a reduction in crimes and there are almost no serious public order incidents. Programmes are available showing the parade routes and listing all the events taking place and maps attached to lampposts also provide information for the bemused spectator. Problems with spectator flow and crushing which were severe on a number of occasions in the 1980s have also greatly reduced.

Carnival has developed within particular social, economic and

political relations in London. It may have drawn upon Trinidadian

styles, but a combination of factors has meant that it has developed,

and will continue to develop, its own distinctive form. Carnival

has become a larger and more successful event, yet for some the

changes have not been for the better believing the commercialism

and organisation have taken the Carnival away from the participants

and reduced its spontaneity. And yet it could also be argued that

such changes have ensured the survival of the event. Carnival

developed in an area of poor housing but Notting Hill has now

become more desirable with new residents voicing concerns about

their property. The organisers have had the difficult task of

addressing the fears of local residents. Had police and organisers

nor developed a good working relationship one wonders how long

Carnival would have lasted in that part of west London. Celebration and Control Carnival is difficult to organise and control. Cohen describes it as a 'a celebration of disorder', that its essence is 'chaotic' (1993:69). It can not be expected that organisers should be responsible tot all that takes place. The police have a duty to ensure public safety but too much control, too much policing, and too many restrictions are counter-productive and impinge upon the nature of Carnival. In many ways there is no harder event for the authorities to deal with since much in Carnival is about raking away the normal structures of society, removing inhibitions, and empowering individuals in the area in which they live. The rules of the street that normally govern the busy roads of Notting Hill are over-turned. Over the past thirty years there have been many who would have liked to see Carnival either stopped altogether or restricted to a stadium or enclosed park. The organisers have had to fight for the right for Carnival to take place. At the same rime the police and the local authority have had ongoing concerns about Carnival ranging from issues of public order to concerns over public health. In addition, as the nature of the area has changed the interests of some local residents have also changed, and whilst Carnival organisers have nor always been able to satisfy some concerns, they have been well aware that it is partly their responsibility to look at issues that might arise. As such the Carnival takes place in a political environment in which there exist a whole range of different interests. There are five areas that appear to be particularly relevant in comparing Carnival with parades in Northern Ireland: liaison, police/organiser co-ordination, stewarding, residents and resources. Liaison: Relationships between the local authority, the police, other public agencies, residents and organisers has never been easy and even in 1997 there were disagreements and problems. Since the late 1980s those organisations involved in the event have signed a 'Statement of Intent and Code of Practice' which, though not legally binding, acts to create a common understanding over the conduct of the various agencies involved. The code of practice specifies such things as agreed routes, noise levels, close down times, safety zones and pedestrian only zones, the licensing of street traders, and the placing of road signs, while the 1996 Statement of Intent suggested that signatories would:

There are also regular meetings between different agencies, although a liaison group including residents and the Chamber of Commerce broke down in the last year. Public meetings to allow organisers to liaise with residents are held annually. That is nor to say that relations have run smoothly but it has certainly given interest groups the ability to make their difficulties known. Police/Organiser Co-ordination: A central feature of the changes that have taken place at Carnival has been the relations between the police and organisers. In the 1970s and 1980s Carnival acted as a barometer for racial tensions in the city. There is no doubt that over the last ten years the Metropolitan Police have placed considerable efforts on trying to improve the situation. A special section was set up which deals with Carnival all year round and those officers work closely with the organisers, sharing information and resources. The structure of management on the day involving police and organisers has also developed over the years. The police have a command structure that liaises with the organisers at the different levels. The 'Gold' control centre used to be at a local school which particularly suited organisers but it is now located at Scotland Yard. The police have an officer at the Carnival office and there is a phone line which residents can call if they have any problems. Carnival itself is divided into particular sectors in which officers co-ordinate with organisers in their particular area. By maximising communication at all levels it becomes possible to minimise the chance of misunderstanding the actions of either participants or police officers. Stewarding: In an ideal situation much of the control of Carnival would be done by stewards. Good stewarding means that the police can be less visible without reducing public safety. At present between 120 and 170 stewards are paid about £90 each and given food and a uniform. The stewards are trained by the police and other emergency services prior to the event. Forty-five stewards, known as Route Managers, are responsible for the movement of the Carnival procession. Each steward is allocated a sector, which coincides with the police sectors and the chief steward liaises with the officer in charge of that sector. It is pointed out to stewards that they must assist police officers and behave responsibly. Both the organisers and police officers expressed concerns about the reliability of stewards. For stewarding to work well it must strike the correct balance of providing knowledgeable direction without becoming either too authoritarian or getting too involved in the event. There is also an issue as to whether you employ outsiders or locals. It would in principle be possible to hire from agencies that run stewarding at large sports events and rock concerts, but as well as increasing the likelihood of getting insensitive stewarding, it is also expensive. On the other hand, detached outsiders are less likely to get drawn into the revelry of the Carnival. The quality and training of stewards is an ongoing problem, for example one participant felt the stewards did not do enough to protect the floats or the performers. However, the need for good stewarding is recognised by all concerned as an essential requirement for a successful Carnival. Residents: Many residents look forward to the Carnival and get involved in some way. However, there are contradictions between the right of people to hold a Carnival and the rights of residents to live peacefully, to retain access to the area and to have their property protected. Anyone who has visited Carnival will know how difficult it is to move in and out of the Notting Hill area, how noisy the event can be, and how it can spill from the streets onto private property. Whilst the organisers recognise some responsibilities and declare sympathy for residents, it would be financially impossible for them to be liable for damage that might be caused. Policy therefore has been aimed at communication and prevention. Public meetings are held at which residents are able to air grievances and at Carnival time a telephone line is available through which residents can contact organisers and police. Resources: As with all events of this nature money is an issue. How much should an event that can bring in money through sponsorship cost institutions of the state and agencies of the local authority? It costs the local council £100,000 for toilets and £60,000 to clear up afterwards. Notting Hill Carnival Ltd receives some money from Kensington and Chelsea, other London Boroughs, the Arts Council, from sponsorship and franchising and from street trading. But the demands on that money come from both the requirements of agencies to help pay for organising the events and from participants who feel that money should go towards helping them prepare elaborate costumes and floats.

The use of resources is a significant political issue. Organisers,

participants, sponsors, local businesses, police and emergency

services, local authorities and residents all have different and

often competing interests. The objective has been to give people

their rights and the facilities to hold the Carnival whilst ensuring

public safety and security. Conclusions Notting Hill Carnival is a large, complex event that has adapted to changing social circumstances since its inception in the mid-1960s. The event raises a series of issues over tights and responsibilities that are pertinent to issues in Northern Ireland. Organisers and participants view it as their right to hold the Carnival and it plays an important role in the artistic expression for many within the West Indian community. Yet the event presents difficulties for residents and businesses in the area and creates costs for local and government agencies. Carnival has become a focus for police community relations over the years. For the Metropolitan Police it is an expensive and difficult event to police, combining as it does a large number of people in confined streets for a somewhat chaotic and anti-authoritarian festival. Carnival has been a focus for the expression of opposition and defiance towards the police, sometimes resulting in significant civil disturbances. Both the police and organisers have recognised that the future of Carnival depended upon improving the relationship between organisers, participants and police. Since the early 1990s the relations between the police and Notting Hill Carnival Ltd. have been good. This process has not been easy, is not without its critics, and may change in the future, but through good communication and liaison difficult issues over the management of the event have been worked out. Both organisers and the police have had to change the way the Carnival is run and controlled. A number of methods have developed that have attempted to improve the relationships that surround the Carnival. (i) A Statement of Intent and Code of Practice has been drawn up, which though not legally binding gives those involved an area of their responsibilities. (ii) Public meetings are held to allow residents to voice their opinions to organisers. (iii) A liaison group worked to try and bring together interested groups. (iv) The police and Carnival organisers work closely together and are prepared to share information. Changes in the way the Carnival has been organised have allowed the event to attract greater outside funding and sponsorship. Increased commercialisation has changed the event in ways that some have welcomed and others have criticised. The Carnival has attracted an increasingly broad range of people from Britain and abroad.

Management of the Carnival on the day has involved a close, structured,

relationship between the police and organisers, the provision

of trained stewards, and a telephone line dedicated to problems

that residents might have. The Loyal Orders in Liverpool Although the Orange Order has never been as strong in England as in Northern Ireland and Scotland, it has played a significant role in the political culture of Liverpool. Like Orange parades in Northern Ireland parades in Liverpool have reflected changing social and political circumstances. In the 1930s concertina bands were prominent in the demonstrations, reflecting the strong maritime links in the city. Until the late 1960s sectarian divisions in the city were such that a Protestant Party was represented on the local council and up to 30,000 people would watch the Twelfth parades with more than one hundred lodges taking part. Members of the loyal orders recount clashes with Catholics in the London Road and Bullring area as recently as 1986. However, the inner city has changed dramatically as a result of slum clearance programmes and many communities have been dispersed to towns outside Liverpool. There are now less than seventy lodges, including women's lodges, in the district. The Orange Order in the Liverpool and Southport area holds about eighteen parades a year, whilst the Black Institution has four and the Apprentice Boys hold three. All but four of the Orange and Black parades are Sunday church parades, as are two of the three Apprentice Boys parades. By far the largest event is the Twelfth of July in Southport. Three feeder parades take place in Liverpool before Orangemen go to Southport where they meet with other brethren from the north-west for a joint demonstration. There are return parades in Liverpool in the evening. It is customary for two children to be dressed as William and Mary for the day. Members of the Order see the Twelfth in Southport as a family day out. There are twelve bands in the Liverpool North End area, most are flute bands and are directly connected to Orange lodges in the city. Unlike in Scotland or Northern Ireland members of bands raking part in an Orange parade must be members of the Orange Order but as in Scotland and Northern Ireland bands must follow certain conditions of engagement. These include requirements on types of uniform and the use of regulation marching steps. There are also clauses which requires bands not to play tunes 100 yards either side of a hospital, church or Cenotaph, banning the drinking of alcohol whilst in regalia, and a clause forbidding the playing of party runes, including the Sash, on a Sunday.

There is also an Independent Orange Order, founded in 1986 after

a dispute within the Orange Order over the right to carry 1912

UVF flags. The Independents have less than a dozen parades each

year. There are also six independent loyalist bands. These march

with both the Apprentice Boys and the Independent Orange Order.

Policing the Parades Public order legislation requires that seven days notice be given before any procession takes place. However, in Liverpool members of the Orange Order meet with the police as early as February or March to discuss any problems that arose at the previous year's parade and any changes that might be needed. The Order also provides the police with a full list of parades planned for the forthcoming year and a list of the lodges and bands expected at each event. In general the police felt that problems over parades were being reduced, but they identified a number of issues that remained problematic. The Twelfth parade in Southport is not always easy because there are a lot of holiday makers in the town who know little about Orange parades and who sometimes cause problems if they walk through the ranks of the parade. The police felt that it was not always easy to find a balance between the rights of marchers and the rights of people to go about their business. As such, the police are keen that the Orangemen are aware of this and are patient with the general public. There are also a few problems on the return parades in Liverpool as a number of the people who gather to watch are often the worse for drink. While there is no need to close any roads in Liverpool for the morning processions, they do close two roads in the evening. Although the police like at least one steward for every 50 people, they would be nervous of having stewards deal with anyone not in the procession. There have been no disputes with local residents since 1986 but the relationship between the Orange Order and Independent Orange Order is so poor that arrangements have to be made to keep the two events separate in both Liverpool and Southport. This means liaising to check that buses do not arrive in Southport at the same time. Also in recent years, there have been problems with fascist groups such as the National Front and Combat 18 attaching themselves to loyal order parades. There were incidents at a pub in Southport in 1996 requiring the use of the riot squad. However, senior members of the Orange Order made it clear that they would nor tolerate members of Combat 18 in the Institution and the police believe that C18 just attaches itself to the event to raise irs own profile.

In general the changing social circumstances have meant that there

are fewer problems over Orange parades in Liverpool than there

used to be and relations between the Orders and the police are

now very good. In Liverpool many of the customary routes in the

city are less populated than they would have been in the past

and in Southport the main concerns are with the interests of tourists

and local businesses. Conclusions As social and political circumstances change the environment in which events are policed can become quite different. In Northern Ireland the policing of Orange parades has become increasingly more problematic with political and residential changes. In Liverpool the events seem to be less tense than in the past and any problems are more to do with crowd control, the use of alcohol and the interests of tourists and businesses. The police were particularly appreciative of the co-operative attitude of the Orange Order in contacting them at the start of the year to make arrangements for forthcoming events.

Democratic Dialogue {external_link} |