'Burntollet' by Bowes Egan and Vincent McCormack[Key_Events] Key_Issues] [Conflict_Background] PD MARCH: [Menu] [Reading] [Summary] [Background] [Chronology] ['Burntollet'] [Sources] Text: Bowes Egan and Vincent McCormack ... Page Compiled: Fionnuala McKenna The following text has been contributed by the authors, Bowes Egan and Vincent McCormack, with the permission of LRS Publishers. The views expressed in this chapter do not necessarily reflect the views of the members of the CAIN Project. The CAIN Project would welcome other material which meets our guidelines for contributions.  BURNTOLLET

BURNTOLLETby Bowes Egan and Vincent McCormack (1969)

Published by:

paperback 64pp

Photographs by:

by Bowes Egan and Vincent McCormack

OPPONENTS of the Northern Ireland government accuse it of operating a police state. The Ulster Unionists, who have held control for nearly half a century, make automatic denial each time this charge is urged. Undocumented allegations and blanket disclaimers do not help towards fair assessment. For seven months we have examined what happened during a Civil Rights march from Belfast to Derry. We have also looked to the aftermath of this demonstration, its consequences, and action taken by the authorities. We are not primarily interested in reciting what happened to students and other young people who set out on the road, hoping to break through barriers of religious bigotry by directing attention to social and economic issues. We have tried to produce a study of Northern Ireland government in action. During their march the walkers learned much of police behaviour and political attitudes through a series of sharp object lessons. We have tried to establish facts, identify participants, and assess the parts they played. The Northern Ireland unit was created in 1920 to appease the fears of a substantial Protestant majority faced with the prospect of inclusion in a Catholic-dominated, all-Ireland state. The Belfast Parliament was given control of matters of local importance, though the British Parliament retained wide powers to intervene. These have not been exercised. From the outset, political attitudes in the new unit were wedded to religious persuasion. Critics argue that this has been disastrous for most of the people. It benefits only the ruling caste within the Ulster Unionist Party. This body is assured of continued power by the adherence of the majority of all classes of Protestants. As this power relies upon the enduring nature of old fanaticisms, official antipathy, previously reserved for those who were opposed to the existence of the Northern Ireland state, now extends to those who campaign against the religious divide. We offer no exhaustive assessment of how the Unionist Party has governed during 50 years of near-absolute power, but seek to tell what we have discovered about the rule of law in Northern Ireland. The incidents described raise important questions about police and governmental partiality, and about the use of mobs to implement official policy. Our description should allow each reader to decide whether the appellation police state" should be applied to this area, and will permit him to assess how well the government has adhered to the principles underlying one of the most potent and cherished Unionist catch-cries: "For civil and religious liberty".

'From pantomime to near-pogrom' A GROUP of about forty young people gathered outside Belfast City Hall towards nine o'clock on the morning of January 1st, 1969. Casually dressed and casually organised, they grouped round placards calling for equal voting rights, fair housing allocations, increased employment, and repeal of Northern Ireland laws limiting individual freedom. One large banner identified the purpose of the meeting as a Civil Rights march. Another indicated that the marchers were adherents of the People's Democracy, a loosely-organised movement campaigning for social justice. At that time most of the movement's supporters were students, and they made up the majority of the group now waiting for the start of a seventy-five mile, four-day walk to the City of Derry. The objectives proclaimed on the demonstrators' banners might have seemed innocuous enough, and unlikely to give offence to any but arch-reactionaries. Yet a crowd of hostile people was gathering. On the opposite side of the road, Major Ronald Bunting was marshalling a group of his followers round a Union Jack and an Ulster Flag. Scenting subversion in any movement critical of the Unionist government, Bunting had proclaimed his intention of "harassing and harrying" the four-day march. To achieve this purpose he had called out the support of his own organisation, "The Loyal Citizens of Ulster", and about seventy men and women had responded. Almost immediately there was a scuffle. Patricia Drinan, a student at Queen's University, Belfast, describes how she saw it: "I was carrying one end of the Civil Rights banner. As we left the City Hall, I felt a sharp tug from the other end of the banner. Some women were shouting, 'Cut it - cut the banner'."Another eye-witness gave his impression of this fracas: "The boy holding the other end of the banner was knocked to the ground and kicked. Immediately another student moved to take the supporting pole and the attackers desisted. The few policemen watched impassively until the disturbance had blown over. Then they made some show of providing protection. No steps were taken by them to alert reinforcements waiting in a police tender down a nearby side street, and no attempt was made to discover the identity of attackers."Flourishing their flags, Major Bunting and his men swung onto the roadway, and led the procession. Along the Belfast pavements other "Loyal Citizens" had assembled. Their attitude, and that of Bunting's men in front, is described by Eddie Toman, a postgraduate student at the University of Edinburgh: "They kept up a constant flow of obscenity and invective. Referring to the marchers' call for equal voting rights, and coupling this with a pejorative term used to describe Catholics, they chanted out a counter slogan, 'One teague, no vote'. The women screamed out 'Paisley, Paisley, Paisley' and 'Ask the Pope to let you have a pill'. More militant, the men undertook to 'Give us civil rights all right', and one of Bunting's immediate cronies assaulted me on the Glengormley road. The police, who were supposedly protecting our legal march from interference, made no attempt to discourage such attacks by the crowd that had taken the road in front and was already, quite deliberately, obstructing and slowing our progress." Another student takes over with his narrative: "We were surprised to see the Union Jack and the Ulster Flag at the head of the march. I moved to the front and took one end of the Civil Rights banner. Two miles further I began to despair that the Buntingites would ever leave. They were slowing the pace of the march considerably, so that we were practically tripping over them. There were no police officers between me and the Buntingite in front. He continually turned to me and used vile language - 'Fenian bastard' and the like. Then, suddenly, on the instructions of Bunting, they moved to the left and dispersed."On the outskirts of Belfast the sustained barrage of abuse died away to be revived only by a group of young people chanting: "One man - no vote!", and by a gang of schoolchildren shouting: "Paisley, Paisley". After a buffet lunch at Dunadry, the march resumed, and by mid-afternoon seventy walkers were approaching the town of Antrim. Just a hundred yards outside the built-up area the main road crosses a railway. Here a very small hostile group of local people had gathered round a man beating on a large-diameter lambeg drum, the "big slapper" associated with Orange Order processions. Ronald Bunting now appeared at the head of this group. Subsequently, he denied any responsibility for planning obstruction. It was, he says, arranged by "farmers, shopkeepers and by landed gentry of the area". Whatever the truth about prior arrangements, Bunting immediately took the lead, acting as more than spokesman for the obstructionists. The police conferred with him, and drew up in a line across the left-hand side of the road, impeding the marchers' progress. The traffic continued to pass to the marchers' right. Michael Farrell, one of the organisers of the march, spoke to County Inspector Cramsie, who had taken charge. He asked this senior police officer to give precedence to a legal procession, remove his men, and clear the opposition from the roadway. From the outset he found that Cramsie's attitude was hostile. He could not bring the march through, he said, and he made it clear that "the people of Antrim" disapproved of the marchers' progress and objectives. Under pressure he agreed to escort them through two by two. Farrell and Erskine Holmes, a prominent member of the Northern Ireland Labour Party, were selected to go first. The latter describes what happened: "We attempted to move forward with the help of the police. As soon as we were in the centre of the hostile crowd, the police vanished. I was punched by one man, who also seized Farrell by the hair, we were jostled by the others, and finally dragged back to the march."Following this fiasco, Cramsie spoke with the hostile group, then returned to tell the marchers that he withdrew his offer to get them through. Patricia Drinan remarks: "It appeared to us that before the police acted they consulted Major Bunting. we asked why this happened. They gave no explanation."Bunting himself subsequently offered a very simple explanation of the county inspector's curious behaviour: "The situation was out of his control. If I had not been there he could have done nothing. I advised him on the tactics he should use ...For three hours the situation teetered from pantomime to near pogrom. The marchers decided to exert pressure that would compel the police to do their duty and clear the way for the legal march, so they formed a human barrier across the road. Bunting charged forward shouting "ambulance, ambulance" and tried to use the space cleared for passage of a mobile X-ray unit to rush his cohorts among the marchers. Invited by the Civil Rights group to explain the reasons for his opposition, Bunting marched through the police cordon and spoke through a loud-hailer. In a curious, disjointed sermonette he spoke of the evil of the church of Rome, and the religion of love, recited a prose poem of a sentimental sort, and then, rambling incoherently, he passed back to the group centred round the Union Jack and the lambeg drum. "The poem was one I was creating at that time," he recalls, "but I have no idea what it was about." "As soon as he finished", writes Gerry May, "a blue Reed Paper Group lorry came out from between the ranks of the police and tried to ram through the marchers. A girl fainted. There was screaming and confusion as the lorry driver kept moving into the crowd. I was in the second row and I saw a policeman kick and punch. He grabbed someone and seemed to be trying to throw him under the lorry. One policeman then tried to hit Michael Farrell, but a number of others held him back."Interviewed later, this lorry driver was distressed and apologetic. He had been instructed by police to drive straight through, he said, and clear a passage for them to follow. Peter Cosgrove, a schoolteacher, was attacked by a policeman: "He kicked out quite deliberately. Shortly after, when the situation quietened, I approached and asked for his identifying number. He grabbed me by the throat, and said that he would charge me with obstructing him in course of his duty, and with assault, if I was not respectful."Numerous marchers testify to the hostile and abusive attitude of the police throughout. One sergeant spent much of his time shouting in unison with the obstructers and adding his own particular appellation, "sewer rats! sewer rats!" Other officers displayed less originality, confining themselves to repetitive obscenities. As darkness fell, the thumping lambeg drum attracted larger crowds, while other hostile groups were recruited from Belfast and from townlands outside Antrim. Many were armed with sticks and other obvious weapons. Despite the fact that such conduct would usually qualify for the stern legal description "behaviour likely to cause breach of the peace", no effort was made by police to disarm them or to prevent encirclement of the marchers. Indeed, County Inspector Cramsie threatened repeatedly to withdraw his men and go home leaving the crowd, which outnumbered the students by five or six persons to one, to do "whatever they think best". At about six o'clock, Raymond Chalker, a recent graduate of Queen's University, came along the roadway in his car. Seeing the confusion, he stopped and got out to speak with students whom he knew, leaving his wife in the car. On returning he found his car surrounded by the hostile crowd shouting: "Students, students, get them, get them." Chalker called to the nearest police officer, a man carrying a blackthorn stick, which indicated that he held a senior rank. He got no help. "You're one of the marchers," said the policeman, and started to walk away. Chalker insisted on his right to police protection, and explained that he was on his honeymoon. The officer relayed this message to the crowd. "Prove it, prove it," they chanted. "Yes," said this senior policeman, obedient to the mob demand, "prove you're not a student." Chalker produced his driving licence. This showed his occupation as engineer. The policeman now turned to the group around the car and announced: "He's all right. He's not a student. He's an engineer." And on this official assurance the crowd faded away, to divert their energies towards other objectives. A number of Civil Rights supporters spent the afternoon with the hostile crowd. One person who had opportunity of talking with the obstructionists and the police gives this account: "The constables and sergeants mixed freely with the group around the Union Jack and lambeg drum. An excited crowd leader explained to a sergeant and two constables how they should 'drag a few over as an example, take them to a barber's shop, shave their heads to the bone, then throw them off the bridge'. One policeman said he thought that would be 'just the medicine'."

'Opposition to the march at Antrim was merely of a passive nature, and no violence or attempt at violence was made by the objectors' - ROBERT PORTER, MINISTER OF HOME AFFAIRS, HOUSE OF COMMONS, JUNE 3rd.

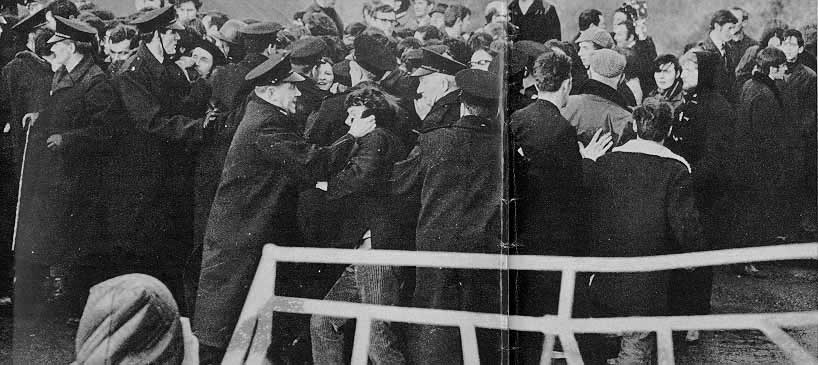

By mid-afternoon on January 1st the march reached a

railway bridge outside Antrim. A small, hostile group was waiting,

gathered round a lambeg drum, the "big slapper" associated

with Orange Order processions. Here it first became obvious that

the marchers could expect little real protection from the police.

With darkness, the throb of the drum drew crowds armed with sticks

and other weapons, and Major Ronald Bunting and his followers

amply fulfilled the major's promise to "hinder and harass"

the march.

Another witness tells how, while the police formed a cordon facing the Civil Rights group, behind this line County Inspector Cramsie engaged in sustained and detailed discussion with the leaders of the opposing crowd. He gives an example of what was said: "At one stage, a constable came through from the Antrim side, approached Cramsie, and reported that a large crowd of newcomers was approaching. 'That's all right,' said a sergeant in attendance, looking down the road, 'they're all our people'."Earlier, the marchers had asked Cramsie to arrange for their transport to the other side of town if he was not prepared to do his duty and clear a way for them to go by foot. He refused point blank, claiming he had no authority to use police vehicles for this purpose. Then Nathaniel Minford, a junior member of the Cabinet, and Member of Parliament for the area, arrived. He cannot have been much surprised at developments because he had, the day before, made a plea for the march to be stopped. In this he had spoken of the opposition which a Civil Rights demonstration would arouse in his constituency. His statement subtracts somewhat from later suggestions that opposition on Antrim Bridge was wholly spontaneous. But Minford, it appeared, had an authority that Cramsie lacked. Quite simply, he instructed the county inspector to take the marchers to their night-time destination in police tenders. Patricia Drinan takes up the story again: "we were told that we were going to be transported to our hall in a police tender. I got into one. It was driven away a bit. Then it stopped. Without any explanation the policeman went away and left us stranded in the middle of the country. We stayed there from ten to fifteen minutes. Then the police came back and drove away again, we went for a great tour of the countryside and arrived a long time later at the hall."

At Antrim Bridge ... a scene of so-called "passive" resistance to the marchers' progress. This ended the first stage of the march. Major Bunting had fulfilled his promise to hinder and harass. He, his followers, and others of like mind, though belonging to different organisations, had obstructed the progress of a legal march. According to well-corroborated evidence, they had used threatening behaviour. Their conduct was not merely likely to cause a breach of the peace, it was openly directed towards this end. They had beaten and hit at a number of marchers. No one was arrested, or subsequently prosecuted for assault. Speaking of the incidents, one marcher said: "When I gauged the overwhelming hostility of the police, from county inspector to constable, I knew that we would get no protection. Even when we got through safely that night, I realised that what had happened would have some dangerous consequences. Bunting must have been most impressed by the readiness of the police to co-operate, consult, to mingle with his gang while presenting a clear opponent's face to the People's Democracy marchers. He had been given open encouragement to continue and intensify his campaign of harassment. we guessed that he would, once more, find ready allies among the Royal Ulster Constabulary. But even after this clear object lesson, I never suspected that this alliance would openly combine in physical attack upon a peaceful march. And I do not think I would be regarded as an exceptionally naive person. . . ."This critical attitude towards the police was not confined to student marchers and casual observers. Dr. Jagat Narain, a lecturer in law at the Queen's University, wrote next day to the Belfast Telegraph: "As a person interested in studying the operation of the constitutional guarantees as to civil liberties in Northern Ireland, I went with the People's Democracy marchers as an observer on the first day of their march to the outskirts of Antrim when it was stopped by the 'loyalists'. Dr. Narain is a specialist in constitutional law, and in legal history. He is also Indian. This last factor made a deep impression on the largely-anonymous writers who directed their comments to him. One Irishman thanked God that he was not of the fifty million Indian untouchables, to which group he presumed Dr. Narain must belong. Less racist was the correspondent who felt: "You should all get a damn good cooling. Our police are a great body of men. They should have put the machine guns on the marchers." A lady who described herself as "True Ulsterwoman" suggested that he betook himself back to his own part of the world, then "shoot out his neck". And one writer confined himself to a single sentiment: "Dirty, stinking Dago wog, go back to your hut in the jungle and leave the police here alone." This last pathetic document merits no mention on its own. But it was written on a sheet of foolscap-sized lined notepaper. On the top was printed the Royal Coat of Arms. This kind of paper is standard issue for internal use in government and administrative circles which include the custodians of law and order. But honi soit qui mal y pense. On June 3rd, Robert Porter, Minister of Home Affairs, told the Northern Ireland House of Commons that prosecutions were not brought against those responsible for the disturbances at Antrim Bridge, for there was no evidence that obstruction was planned. Passing over the question why the lambeg drummer chose that site and time for his music practice, Porter went on to tell that prosecutions were not brought because "the opposition to the march at Antrim was merely of a passive nature, and no violence or attempt at violence, was made by the objectors". In a leading story the next day, The Guardian told how hundreds of opponents maintained a continual string of abuse, and described how Paisleyites tried to wrench banners from the marchers. Paddy Devlin, then Chairman of the Northern Ireland Labour Party, was sufficiently perturbed to direct a telegram to the British Home Secretary, James Callaghan. This read: "Members of People's Democracy on way to Derry denied right to march by extremist thugs at Antrim. Need your help immediately to secure this right."

|

CAIN

contains information and source material on the conflict

and politics in Northern Ireland. CAIN is based within Ulster University. |

|

|

|||

|

Last modified :

|

||

|

| ||