Accord - 'Striking a Balance: The Northern Ireland Peace Process', ed. by Clem McCartney[Key_Events] Key_Issues] [Conflict_Background] PEACE: [Menu] [Summary] [Reading] [Background] [Chronology_1] [Chronology_2] [Chronology_3] [Articles] [Agreement] [Sources] Material is added to this site on a regular basis - information on this page may change The following extracts have been contributed by the authors, with the permission of the editor Clem McCartney, and publisher Conciliation Resources. The views expressed in this chapter do not necessarily reflect the views of the members of the CAIN Project. The CAIN Project would welcome other material which meets our guidelines for contributions.  These extracts are taken from the journal:

These extracts are taken from the journal:

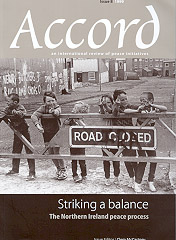

Accord - An international review of peace initiatives

For single issues or subscriptions contact:

Cover photo: West Belfast, early 1980's (Source: Belfast Exposed)

These extracts are copyright Conciliation Resources 1999 and are included

on the CAIN site by permission of the editor, authors and the publishers. You may not edit, adapt, or redistribute changed versions of this for other than your personal use

without the express written permission of the author or the publishers Conciliation Resources. Redistribution for commercial purposes is not permitted.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to the authors of the articles and to Thomas Abraham, Sam Burnside, Tony Catney, Jonathan Cohen, Tommy Gorman, Vasu Gounden, Tyrol Ferdinands, Guus Meijer, Martin Melaugh, Chris Mitchell, Joan Newman, Andy Pollak, Mike Poole, David Stevens and Anjoo Upadhyay for their helpful comments and advice; to Chris McCartney for assistance with the chronology, bibliography and profiles sections; and to the Department for International Development (UK), Community Relations Council (Northern Ireland), and the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation (USA) for their financial support. Published by Conciliation Resources

© Conciliation Resources 1999 Permission is granted for reproduction and use of these materials for educational purposes. Please acknowledge your source when using the materials and notify Conciliation Resources.

UK charity registration number 1055436

Forward

Thomas Abraham

O ne of the most remarkable events of 1998 was the signing of the Belfast Agreement. It was arrived at after a long and arduous process of negotiations, promised to bring to an end one of the world’s longest running conflicts. At the time, it was hailed as a triumph for the process of conflict resolution through democratic negotiations rather than through the power of the gun.The euphoria that surrounded the Agreement evaporated somewhat in the months that followed. It soon became apparent that getting Northern Ireland’s political parties to implement the various provisions of the Agreement was not going to be as straightforward as had been hoped. But despite the inter-party wrangles over the interpretation of key provisions of the Agreement, there is little doubt that there has been a dramatic change in atmosphere in the province. A ceasefire by the main armed groups has more or less held, the level of violence has decreased dramatically, and ordinary people are increasingly getting accustomed to living their lives without the constant fear of disorder. The Belfast Agreement is significant not merely for the people of the province, but for those caught in similar conflicts around the world. While every conflict is unique, shaped by its own particular circumstances, disputes between groups of people over issues of nationality, identity and statehood also have universal elements. This is why it is rewarding to study peace processes in other parts of the world: there are always lessons to be drawn from successful, or even failed peace attempts which can be applied to one’s own situation. There are several elements in Northern Ireland’s path to peace that are worth studying. One of these is the process by which the Irish republican movement gradually changed its tactics from an almost exclusive reliance on armed struggle to trying to achieve their aims through negotiations and the ballot box. The transformation of an armed struggle into democratic political movement is one of the hardest tasks in conflict resolution. This volume provides insights into the conditions and strategies that made this possible in Northern Ireland. It is not only armed groups who have to abandon long held strategies in the interests of peace. Democratic parties have often to make painful compromises as well, as illustrated by the experience of the Ulster Unionists, the principal party of the Protestant, unionist community. The experience of the Ulster Unionists as they ‘travelled that extra mile to reach an agreement', as one of the contributors to this volume puts it, holds valuable lessons. Three governments, Britain, Ireland and the United States played key roles in the peace process. Britain and Ireland, as the two countries directly involved, played a variety of roles at different times ranging from mediation to acting as a proxy for the different parties in Northern Ireland. But by far their most important contribution was to have laid a foundation for peace talks by declaring they were willing to abide by the wishes of the people of Northern Ireland. This created the space for the political parties in the province to decide their own future through negotiations. Perhaps the most striking part of the Belfast Agreement has been the way the principle of consent has been woven into its every strand. The essence of the Agreement is that the future of the province can only be determined by the consent of its people. What is important is that this consent is not mechanically defined as agreement by the majority of the population, but instead as an agreement by the majority of people in both the Protestant and Catholic communities. In other words, Northern Ireland’s future can only be determined on the basis of a genuinely popular consensus that would cut across communal and sectarian divisions. The Belfast Agreement was arrived at through negotiations, endorsed by a popular referendum and backed by the international community. This is a pattern of conflict resolution that is worth emulating. Clem McCartney

W hen the Troubles began in Northern Ireland at the end of the 1960s, one response from the British government was the establishment of a Community Relations Commission to develop strategies to improve relationships between the two communities. The Commission thought that society suffered from a lack of community infrastructure and local leadership and that it was important to create a pool of community activists who would eventually connect across the divide and create a new non-sectarian stratum of society which could develop a new politics.The wider public was in part already involved in political action. The Orange Order, for example, permeated all sections of the Protestant community and acted as an important link between political and civil society. The leaders of the civil rights movement, although mainly middle class and professional, were successful in mobilizing a wide section of the community in their campaign. Their opponents were led by uncompromising Protestants, mainly from the Free Presbyterian Church of Ian Paisley, though participants in their protest rallies also included other disaffected loyalists. Both communities had only limited opportunities for developing a broader political understanding of the situation and street politics remained largely a reflection of traditional sectarian loyalties and identities. The rise of organized community activity It was also true that in other sectors of civil society there was a great deal of disillusionment with politics throughout the 1970s and 1980s. Many who did not support the predominant system of sectarian politics found their sphere of activism in the trade unions, churches, and neighbourhoods, but they had little impact on the overall political situation. Most sectors of society, including the churches, were themselves divided about the most appropriate response to the conflict, and in these circumstances intransigent voices were dominant. Perhaps it was inevitable that violence would muffle the voices of those who support accommodation. Intransigent voices speak a simpler and more forceful message that is easier to understand than the more intricate and less obvious arguments in favour of co-operation and dialogue. It has always been difficult for civil society in Northern Ireland to open up a broader middle ground where a settlement might be more likely to be found.

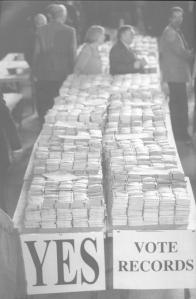

Prophets and reconcilers Cross-community contact was promoted most vigorously among young people and there were a variety of pilot education programmes in schools and summer holiday schemes, not only in Northern Ireland but also in other parts of Europe and the USA. They were sponsored partly by local host groups and in part by the government. Their experience pointed the way for the eventual inclusion in 1992 of a theme entitled ‘Education for Mutual Understanding’ in the core school curriculum. Although the education system remains largely segregated, one of the most striking achievements of civil society groups has been the creation of a system of integrated schools. They started in the 1980s with no official support and are now an established, if small, part of the government-funded education system. On occasions individual church leaders met politicians and paramilitary groups to urge them to end their violence. The business and trade union leadership tended to speak out in favour of the commercial advantages of a settlement. Trade unions organized actions against sectarianism — in particular against the loyalist-organized Ulster Workers Council Strike in 1974 that aimed to bring down the power-sharing assembly — but these efforts had little support. One of the most consistent and innovative organizations in its methods and programmes is Corrymeela, a Christian community with its own residential accommodation in a quiet rural area. Its members were scattered throughout society and were encouraged to work in their own neighbourhoods and local associations to challenge the prevailing nature of politics. It was also one of the few civil society groups which tried to build links and enter into dialogue with political parties. With notable exceptions, such as the Centre for the Study of Conflict at the University of Ulster, the academic community gradually took a professional interest in the conflict — but tended to analyze its nature rather than attempt to provide critical viewpoints for politicians and policy makers. Slow progress There was therefore limited interaction between the more conciliatory sections of civil society and the political process. When a conflict seems intractable, there is often a hope that the stalemate could be broken by movement within civil society. Such a scenario is attractive in affirming the importance of the whole community and in suggesting a way forward when progress at the political level seems impossible. But the experience of Northern Ireland gives little evidence of civil society mobilising to play such a key role. Society remained polarized. There was a growing weariness of the constant hostility and a fear of violence, but the determination not to compromise on core commitments and values remained strong. Developing synergy Perhaps one of the most significant civic contributions was Initiative ‘92, which described itself as a citizens’ inquiry. A group of civil activists established a commission, which sat from 1992 to 1993, to take opinions from the community and political parties on the way forward. It was composed of weighty individuals from Ireland and Britain and was chaired by Professor Torkel Opsahl from Norway. Opinions vary on its impact. Its findings may not have been particularly original, and its lasting contribution may have been its efforts to encourage community groups and individuals to think and discuss the options for the future. As a result the wider community began to have greater confidence in putting forward its views and engaging with the political process and politicians from whom it had felt alienated for so long. For example, the leaders of the seven main coordinating bodies of industry, business and trade unions formed a loose group, known as the G7, through which they developed opportunities for dialogue with politicians. Two local newspapers, identified with the sectarian divisions, began to work together, even printing a common editorial on one occasion. Finding a voice It is noteworthy that the electoral process for selecting the representatives to take part in the negotiations provided an easy opportunity for new groups from civil society to be elected and yet very few civil society groups were formed. Well over ninety per cent of the electorate voted for the existing parties and only one new group, the Northern Ireland Women’s Coalition, was successful. It was able to make a significant alternative input into the negotiations, though it only had one per cent of the popular vote. Towards the end of the negotiations small groups of pro-Agreement activists had begun to engage in a new type of action. Throughout the Troubles opponents of accommodation have made their views known by assembling outside buildings where significant political meetings where taking place. Now those who supported political co-operation and accommodation also began to appear. Their presence reinforced the realization that there was support for inclusive politics. This message was perhaps most important for those opposed to the peace process. Once the Belfast Agreement had been achieved, it had to be ratified by a referendum, and this presented another opportunity for civil society to make its voice heard. The anti-agreement ‘No’ campaign was more vociferous and the pro-Agreement political parties were rather halfhearted in their campaigning. A civil society ‘Yes’ Campaign was quickly organized with members of Initiative ‘92 at its core, and they attempted to create a popular campaign involving local celebrities. The will for a settlement did exist and had some influence over politicians.

International influence

Ideas of conflict resolution and joint exploration of issues, especially that it is possible to find solutions which satisfy the interests of all parties, were beginning to percolate through society and among politicians. A number of initiatives involving politicians and others in off-the-record conflict resolution training or problem-solving seminars were undertaken, mainly by American groups. Their impact is unclear and some of the most intransigent activists, who did not see the need for new alternative approaches, tended to be dismissive of such initiatives. Politicians made a number of visits to countries such as South Africa and met with local leaders from divided communities. Those involved have often said these were their most significant and meaningful experiences, encouraging them to believe that a settlement was possible. The good offices of civil society The experience of the Troubles has been profound for civil society. Many of those who have endured the years of conflict have been energised and become more aware of the nature of their society and the roles they can play in making it function more effectively. A Civic Forum is to be established under the Belfast Agreement to maintain the interaction between civil society and politicians. The lessons already learned and the confidence gained could make a major difference in building a new peaceful society and dealing with the many issues which still exist. Section A — the peace process Bew, P.& Gillespie, P. The Northern Ireland Peace Process 1993 - 1996: A Chronology. Serif, London, 1996 O’Doherty, M. The Trouble with Guns. Blackstaff Press, Belfast, 1998 Fordham International Law Journal. The Belfast Agreement. vol.22, no. 4, April 1999 Gilligan, C. & Tonge, J. (eds.) Peace or War? Understanding the Peace Process in Northern Ireland. Ashgate, Aldershot, 1997 Mallie, E. & McKittrick, D. The Fight for Peace: The Secret Story Behind the Irish Peace Process. Heinemann, London, 1996 McCartney, R. The McCartney Report on Consent. (UKUP) Belfast, 1997 McCartney, R. The McCartney Report on the Framework Document. UKUP, Belfast, 1997 McKittrick, D. Endgame: The Search for Peace in Northern Ireland. Blackstaff Press, Belfast, 1994 McKittrick, D. The Nervous Peace. Blackstaff Press, Belfast, 1996 Mitchell, Senator G. Making Peace: the inside story of the making of the Good Friday Agreement, Heinemann, London, 1999 O’Clery, C. The Greening of the White House, the Inside Story of How America Tried to Bring Peace to Ireland. Gill and McMillan, Dublin, 1996 O’Leary, B. The Nature of the Agreement, John Whyte Memorial Lecture. Queen’s University, Belfast. 1999 Rowan, B. Behind the Lines: the Story of the IRA and loyalist ceasefires. Blackstaff Press, Belfast, 1995 Section B — participants Bruce, S. The Red Hand: Protestant Paramilitaries in Northern Ireland. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1992 Cochrane, F. Unionist Politics and the Politics of Unionism since the Anglo-Irish Agreement. Cork UniversityPress, Cork 1997 Cooke, D. Persecuting Zeal: A Portrait of Ian Paisley. Dingle Press, Brandan, 1996 Drower, G. John Hume. Vista, London, 1996 Moloney, E. & Pollak, A. Paisley. Poolbeg, Swords, 1986 Murray, G. John Hume and the SDLP: Impact and Survival in Northern Ireland. Irish Academic Press, Dublin, 1998 Patterson, H. The Politics of Illusion: A Political History of the IRA. Serif; London, 1997 Porter, N. Rethinking Unionism (2nd edn.) The Blackstaff Press, Belfast, 1998 Porter, N. (ed.) The Republican Ideal. The Blackstaff Press, Belfast, 1998 Sharrock, D.& Devenport, M. Man of War, Man of Peace? The Unauthorised Biography of Gerry Adams. Macmillan, London, 1997 Shirlow & McGovern (eds.) Who are the people? Unionism, Protestantism and Loyalism in Northern Ireland. Pluto Press, London, 1997 Taylor, R. Provos: The IRA and Sinn Féin. Bloomsbury, London, 1998 Taylor, R. Loyalists. Bloomsbury, London, 1999 Toolis, K. Rebel Hearts: journeys within the IRA’s soul. Picador, London, 1995 Section C — background Coogan, T.R The Troubles: Ireland’s Ordeal 1966 — 1995 and the Search for Peace. Hutchinson, London, 1995 Darby, J. Scorpion in a Bottle: Conflicting Cultures in Northern Ireland. Minority Rights Publications, London, 1997 Foster, R. F. Modern Ireland 1960 — 1972. Penguin, 1989 Hennessey, T. A History of Northern Ireland 1920 - 1996. MacMillan, London, 1997 Lyons, F.S.L. Ireland Since the Famine. Fontana, London, 1973 O’Leary, B. & McGarry, J. The Politics of Antagonism: Understanding Northern Ireland. The Athlone Press, London, 1996 O’Malley, R The Uncivil Wars: Ireland Today. The Blackstaff Press, Belfast, 1983 Pollak, A. (ed.) A Citizen’s Inquiry: The Ophsahl Report on Northern Ireland. The Liliput Press for Initiative ‘92, Dublin, 1992 Stewart, A.T.Q. The Narrow Ground: Aspects of Ulster, 1609 - 1969. The Blackstaff Press, Belfast, 1977 Stevens, D. A. Briefing Paper on Ireland. Irish Council of Churches, Belfast, 1997 Whyte, J. Interpreting Northern Ireland. Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1990

Electronic resources CAIN project Irish Times ‘The Path to Peace’ Northern Ireland Office Irish Government University of Ulster Library

From the back cover:

The Northern Ireland peace process Accord 8 explores the factors that convinced those on all sides of the Troubles that talking was a better alternative to fighting and it outlines the impact of history on current aspirations. In describing the development of an environment for peace negotiations it analyses the complex forces underlying the current situation and those aspects of the Agreement that have either facilitated the political process or caused problems with implementation. Key players in the peace process, from a wide range of political backgrounds, offer their perspectives on the Agreement and share their hopes and fears for the future of peace in Northern Ireland. These unique insights shed new light on one of the most publicized peace processes of recent years. The Accord series The Accord series offers an authoritative and balanced review of war and peace processes. Each issue contains narrative and analysis by national and international experts, historical background and texts of peace agreements. ‘This [the Georgia-Abkhazia issue] is really masterly. I feel now, for the first time, that I understand something of the situation. But over and above that, it provides a model of analysis and reporting that most journalists should heed.’

Adam Curle ‘I would like to congratulate you on your pioneering work. The publication captures a broad audience, as it appeals to those who have no prior knowledge about the subject as well to those who require further in-depth information. I was especially pleased by the fact that you gave both sides a chance to present their views.’ Angela Kane ‘This is a highly informative, concise and useful reference ... the Accord series has allowed comparative analysis and reflection; while the details of the situations often vary greatly, there are recurring themes in almost all situations, allowing us to learn from different cases... It should be essential reading for the relevant negotiators and policy-makers.’

Max van der Stoel The full text of all issues in the Accord series can be found on the Conciliation Resources website at http//www.c-r.org {External_Link}

|

CAIN

contains information and source material on the conflict

and politics in Northern Ireland. CAIN is based within Ulster University. |

|

|

|||

|

Last modified :

|

||

|

| ||